Uneori, când politica devine prea învolburată,

ai nevoie de poezie ca să o navighezi fără să îți pierzi mințile.

De pildă, atunci când milioane de turci au ieșit în stradă

și aproape au dărâmat regimul autoritar

dar până la urmă nu au făcut decât să grăbească

alunecarea spre dictatură.

Sometimes, when politics gets too chaotic,

you need poetry to make sense of it.

Like the time when millions of Turks took to the streets

and almost brought down the authoritarian regime

but in the end they only rushed

the descent into dictatorship.

Ne simțeam puternici.

Simțeam că o să schimbăm ceva.

Credeam că vom câștiga.

spune Volkan, un tânăr turc

care s-a aruncat trup și suflet

în protestul din Piața Taksim, în 2013.

A fost cel mai fericit moment al vieții mele.

A locuit o săptămână în parc.

A făcut o bibliotecă liberă

și a cărat răniți.

Prea mulți au fost răniți,

prea mulți oameni au murit,

prea mulți și-au pierdut ochii.

Strigau.

We felt powerful.

We would change something.

We thought we could win.

says Volkan, a young Turk

who jumped in over his head

in the Gezi Park protest of 2013.

It was the happiest moment of my life

He lived in that park for a week.

He built a free library for protesters

and he carried away the wounded.

Too many were injured,

too many people died,

too many lost their eyes.

They screamed.

Autoritățile au așteptat o zi ploioasă

și au atacat.

Era dimineața devreme.

N-am putut să le ținem piept

decât vreo două ore.

Apoi am fugit.

Sute de morți.

Sute de mii de oameni epurați.

Sute de ziare desființate.

Tăcere.

Acum,

tinerii revoltați

publică poezii revoluționare

în reviste scoase la xerox.

The government waited for a rainy day

and then it attacked.

It was early in the morning.

We could only hold them back

for a couple of hours.

And then we ran.

Hundreds of people killed.

Hundreds of thousands of purges.

Hundreds of newspapers crushed.

Silence.

Now,

angry young men

publish revolutionary poems

in xeroxed magazines.

Nu vă imaginați că poezia

e doar pentru puștani înflăcărați.

Erdogan însuși,

înainte să fie liderul suprem,

a făcut pușcărie pentru o strofă.

Iat-o:

Moscheele sunt cazărmile noastre,

cupolele sunt căștile noastre,

minaretele sunt baionetele noastre,

iar credincioșii sunt soldații noștri.

Nu e cine știe ce,

dar nu merita pușcărie pentru asta.

Și nici poporul turc nu merita

ce i-a făcut după ce a ieșit.

Don’t think that poetry

is only a thing for fiery young men.

Erdogan himself,

before being supreme leader,

went to jail for reciting a verse.

This one:

The mosques are our barracks,

the domes our helmets,

the minarets our bayonets,

and the believers our soldiers.

Not great, not terrible

but he didn’t deserve prison for this.

And neither did the Turks deserve

what he did after he got out.

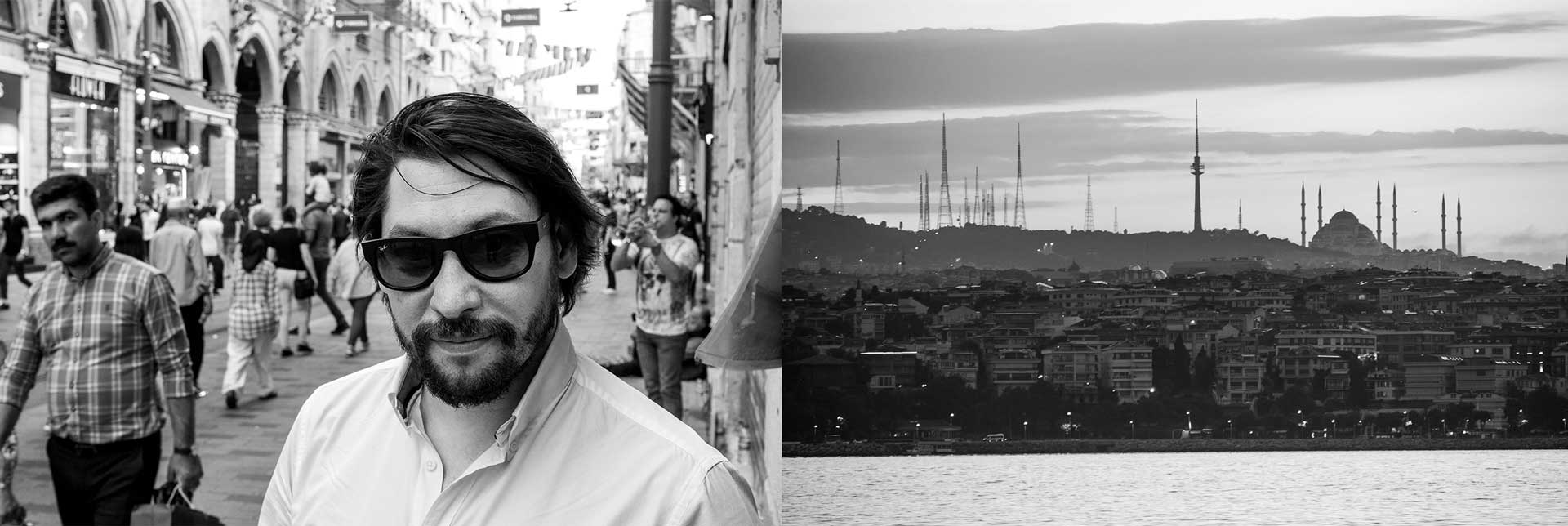

Volkan e mare fan Tristan Tzara

și asta se vede în frizura lui,

în camera lui, în viața lui,

în revista pe care o face.

Pune în ea speranțele generației sale.

Se numește VOID.

Ø

Primul lui protest a fost

la vârsta de trei ani.

L-a dus maică-sa,

care era profesoară în Adana.

Era o demonstrație pentru

un jurnalist asasinat.

O vreme a vrut

să se facă și el jurnalist,

dar a ales viața.

A mers în Istanbul să studieze film.

Locuia în Taksim,

lucra într-un bar tot acolo,

acolo și-a cunoscut prietenii

și tot acolo a încercat

să facă revoluție.

Ø

Greu să trăiești

în Istanbul după asta.

Poliție peste tot.

Societatea islamică

pune presiune

pe tine.

Mintea mea

încearcă să

se ascundă.

Volkan is a big fan of Tristan Tzara

and you can see it in his hairstyle,

in his room, in his life,

in the magazine he’s editing.

He pours into it the hopes of his generation.

It’s called VOID.

Ø

He went to his first protest

when he was three years old.

His mother took him,

she was a teacher in Adana.

It was a demonstration for

a journalist who was killed.

For some time he wanted

to be a journalist himself,

but he chose life.

He went to Istanbul to study film.

He lived on Taksim,

he worked in a bar there,

that’s where he met his friends

and that’s where he tried

to make a revolution

Ø

Hard to live

in Istanbul after this.

Police everywhere.

The islamic society

puts pressure

on you.

My mind

always tried

to hide.

Nici nu mai vrem să mergem pe-acolo

ca să nu ne aducem aminte.

spune James Hakan Dedeoğlu,

un tovarăș de-al lui Volkan

care face de 15 ani o revistă

serioasă de cultură.

După anii ‘80,

marcați de o lovitură de stat militară,

cultura turcă s-a deschis în anii ’90

către Occident. Miezul era la Taksim.

Era dur, haotic.

Toată lumea avea o voce.

Când a venit Erdogan la putere,

a păstorit creșterea economiei

și o epocă de capitalism islamic.

Peste tot s-au construit

mall-uri și moschei.

Așa a început revoluția din Taksim,

cu proteste împotriva demolării

unui cinema istoric.

Poliția a atacat regizorii,

i-a împroșcat cu gaze lacrimogene.

Ø

Gezi a fost atât de puternic,

dar s-a sfârșit atât de rău.

A fost o înfrângere.

Oamenii s-au retras în cartiere.

Au început să acționeze local.

People don’t even want to go back there

so they won’t remember.

says James Hakan Dedeoğlu,

a friend of Volkan,

who edited a proper cultural magazine

for the last 15 years.

After the ‘80s,

marked by a military coup,

Turkish culture opened up in the ’90s

to the West. Its core was Taksim.

It was rough, chaotic.

Everybody had a voice.

When Erdogan came to power,

he triggered an economic boom

and an era of islamic capitalism.

Everywhere they built

malls and mosques.

That’s how the Taksim revolution began,

with protests against the demolition

of a historic cinema.

The police attacked film directors,

sprayed them with tear gas.

Ø

Gezi was so strong, so powerful,

but it ended in a bad way.

It was a defeat.

People retreated to their neighbourhoods.

They started doing things locally.

Poezia a făcut un salt!

strigă poetul Şevket Kağan Şimşekalp

în timp ce ascultă Metallica

la maxim.

În subterane

e o reacție foarte puternică

la dictatura asta.

Crede că întreaga societate

suferă de ceva boală mintală

și asta e șansa ei să se trezească.

În anii ‘80,

s-a născut o generație apolitică.

Au fost creați oameni adormiți.

Nu s-au trezit până la Gezi.

Poetul e cuprins de entuziasm,

vorbește de renașterea poeziei

ca programare pe calculator,

apoi se prăbușește:

Poeții de avangardă din estul țării

sunt băgați la pușcărie sau executați...

Poetry made a jump!

shouts poet Şevket Kağan Şimşekalp

while listening to Metallica

at full volume.

In the underground

there’s a very strong reaction

to this dictatorship.

He thinks the whole society suffers

from some kind of mental illness

and this is its chance to wake up.

In the ‘80s,

an apolitical generation was born.

Sleeping people were created.

They did not wake up until Gezi.

The poet gets filled with enthusiasm,

he claims the rebirth of poetry

as computer programming,

then falls into himself:

Avant-garde poets in the East

are either put in prison or hanged...

Poezia politică e o tradiție locală.

spune Efe Duyan,

poet și profesor

la Universitatea de Arte.

Poezia e politică din secolul 19.

Elitele erau poeți.

Au văzut Revoluția Franceză

și s-au întors cu idei despre naționalism

și modernism și futurism.

Altă tradiție locală:

să bagi poeții la pușcărie.

Nâzım Hikmet,

cel mai important poet,

a fost condamnat la 28 de ani.

Tot ce scria venea ca un șoc.

În anii ‘60 și ’70,

la fiecare protest

erau poeți care recitau.

Efe Duyan a fost și el arestat

în timp ce participa la proteste.

Acum 10 ani am stat

10 zile în arest.

M-au săltat,

m-au bătut ca nebunii.

Atunci îți dai seama

ce sunt ei cu adevărat.

Ei nu cred

în vrăjeala asta cu democrația.

Taksim l-a schimbat pe Erdogan.

Îi era așa de frică de revoluție

că a renunțat la masca de democrat.

A devenit un dictator pe bune.

Mă opun pe față,

dar încerc să o spun cu grijă.

Și studenții ar putea merge la poliție

după curs. Se mai întâmplă.

Încerci să-ți păstrezi speranța

încerci să trăiești

să ieși în oraș

să porți fustă

să ceri un dram de justiție

poate mai puțină corupție...

Am avut tot timpul sentimentul

că trebuie să schimb lumea.

Încerc să rezist.

Scriu poezie.

nici poeziile

ca planurile mărețe

nu pot fi uneltite în detaliu

Political poetry is a local tradition.

says Efe Duyan,

poet and professor

at the University of Arts.

Poetry is political since the 19th Century.

The elites were poets.

They saw the French Revolution

and came back with ideas of nationalism

and modernism and futurism.

Also a local tradition:

sending poets to prison.

Nâzım Hikmet,

the most important poet,

was sentenced to 28 years.

Everything he was writing was a shock.

In the ‘60s and ’70s,

every demonstration

had poets reading.

Efe Duyan was himself arrested

while attending demonstrations.

10 years ago I spent

10 days in prison.

They took me in,

beat me like crazy.

That’s when you see

what they really are.

They don’t believe

in this democracy bullshit.

Taksim changed Erdogan.

He was so affraid of the revolution

he quit the role of democrat.

He became a proper dictator.

I’m openly opposed,

but I try to say it in a careful way.

Even students could go to the police

after the course. These things happen.

Trying to stay hopeful

trying to live

drinking out

wearing a skirt

asking for some basic justice

maybe less corruption…

I always had this feeling

that I have to change the world.

I try to resist.

I write poetry.

revolutions too

like grand plans

can’t be plotted in great detail

Uneori,

nici nu e nevoie să scrii tu poezia

ca s-o pățești.

Doctorul Altay Öktem

a fost forțat să-și dea demisia

din spitalul din Istanbul în care lucra

pentru că avea o colecție de reviste ilegale.

Colegii m-au văzut că strâng reviste

și m-au întrebat:

Ești satanist?

În vremea aia era o vânătoare de sataniști.

Poliția făcea liste cu roacheri.

Îi săltau pe stradă pe cei cu

plete sau tricouri negre.

El a scăpat cu demisia

și a ajuns să scrie cărți despre

cultura subterană.

Când era mic,

nu-i plăcea fotbalul.

Îi plăcea să citească.

Taică-su era ofițer,

și l-a trimis la liceul militar.

Nu-mi place armata!

Eram deprimat.

Când aveam puțin timp, citeam poezii.

Poeziile m-au ajutat.

Era haos prin Turcia.

Mulți oameni au fost omorâți în anul ăla,

1978.

În 1980 a fost o lovitură de stat militară.

M-au dat afară pentru că eram socialist.

Aveam 16 ani!

Nici nu știam ce-i ăla socialism.

Era haos.

Cum puteam să fac bani?

Am mers la medicină,

că-mi place să ajut oameni.

Meseria mea era foarte sângeroasă.

Vedeam mulți morți.

În timpul ăsta, citea Ginsberg

și Edgar Allan Poe.

Sometimes,

you don’t even have to write it yourself

to get in trouble.

Doctor Altay Öktem

was forced to resign

from his hospital in Istanbul because

he owned a collection of illegal magazines.

My colleagues saw I was collecting fanzines

and asked me:

Are you satanist?

In those times they were on a satanist hunt.

Police made list of rockers.

They picked them up on the street

if they had long hair or black shirts.

He got away by resigning

and ended up writing books about

underground culture.

When he was little,

he didn’t like football.

He liked to read.

His father was an officer,

so he sent him to a military highschool.

I didn’t like militarism!

I was depressed.

When I had a bit of time, I read poetry.

Poems helped me.

Turkey was very chaotic.

Lots of people were killed that year,

1978.

In 1980 there was a military coup.

They fired me because I was a socialist.

I was 16 years old!

I didn’t even know what socialism means.

There was chaos.

How could I earn money?

I went to medicine,

because I like to help people.

My job was very bloody.

Lots of dead people.

In the meantime, he read Ginsberg

and Edgar Allan Poe.

A început să colecționeze fanzine,

reviste informale trase la xerox

și distribuite din mână-n mână.

Aveau idei interesante,

dar nu puteau să le publice în reviste legale.

Aveau și ei familii…

Protestul din Taksim a fost momentul

în care pasiunea i-a acaparat viața.

A ieșit în stradă cu toată familia.

În Turcia, nimeni n-a mai simțit așa libertate.

Doar în parcul Gezi m-am simțit liber.

Ei cred că suntem teroriști.

De fapt, suntem cea mai bună parte a Turciei.

Trăim ca europenii.

Bem bere, facem sex...

Ne-am pierdut utopia.

Avem destule distopii, dar nici o utopie.

Trebuie să ne luptăm cu guvernul.

Creionul este o armă.

He started to collect fanzines,

informal xeroxed magazines

passed around peer-to-peer.

They had interesting ideas,

but couldn’t write them in legal magazines.

They had famlies, you know...

The protest in Taksim was the moment

when his passion took over his life.

He went into the street with his family.

In Turkey nobody felt freedom like this before.

Only in Gezi park I feel myself free.

They think we are terrorists

Actually, we are the best side of Turkey.

We live like Europeans.

We drink beer, we have sex...

We lost our utopia.

We have lots of dystopias, but no utopia anymore.

We have to fight with the government.

The pencil is a weapon.

Mă trezesc dimineața târziu.

Aoleu, e ziua alegerilor!

Cât dormeam eu,

au votat deja milioane de oameni.

Îmi vuiesc în cap toți cei

cu care am vorbit în ultimele zile.

Nu înțeleg cum pot să trăiască așa,

între teroare și exaltare.

Zilele trecute am fost

la un miting al opoziției

și am văzut milioane de turci

cum flutură ca steagurile

și răcnesc ca niște difuzoare

prin care vorbește contracandidatul,

un profesor de fizică mustăcios

ce scria cândva poezii erotice.

Ai auzit vreodată milioane de oameni

spunând câte un cuvânt la unison?

Tremură dealurile.

Răsună marea Marmara.

Și mie încă-mi răsună-n cap,

filtrat prin berile și manelele turcești de aseară,

cum se luptă perpetuu cu dușmanlar.

I wake up late in the morning.

OMG, it’s election day!

While I was sleeping,

millions of people already voted.

My head is roaring with all

the people I’ve been talking to.

I don’t understand how they can live

like this, between terror and exaltation.

Last days I’ve been to

an opposition march

and I saw millions of Turks

fluttering like flags

and shouting like loudspeakers

amplifying the contender,

a mustached physics teacher

who once wrote erotic poems.

Did you ever hear millions of people

shouting together one word at a time?

The hills are trembling.

The Marmara sea resounds.

And it still resounds in my head,

through last night’s beers and Turkish songs

about fighting eternal enemies.

Ies pe străzi,

e plin de puști automate,

ca la mitingurile lui Erdogan,

care a colindat țara într-un

autobuz tapetat cu fața lui imensă,

înconjurat de o armată personală,

cu elicoptere zburând pe deasupra

și lunetiști mustăcind pe acoperișuri.

Soldați înarmați aruncau jucării

la copiii spânzurați de garduri.

Oameni însuflețiți de ideea

că în orice alt loc nu sunt în siguranță.

Nu se mai poate așa,

îmi spune Volkan,

care în general crede că

toate partidele-s aceeași mizerie,

dar la tura asta n-ai cum să stai acasă.

E totul sau nimic.

Mergem la secția de vot

împânzită cu portrete ale sultanilor

și camere de supraveghere.

Apoi mergem la o înmormântare.

I go out into the streets,

automatic rifles everywhere,

like it was in the marches for Erdogan,

who toured the country in a bus

featuring his huge face,

surrounded by a personal army,

with helicopters buzzing around

and snipers mumbling on rooftops.

Armed soldiers were throwing toys

to children hanging on fences.

People animated by the thought

that all the other places are not safe.

This can’t go on,

Volkan tells me.

He used to think that

all the parties are the same crap,

but this time you just can’t stay on the side.

It’s all or nothing.

We go to a voting place

filled with portraits of sultans

and security cameras.

Then we go to a funeral.

Un tovarăș de-al lui,

artist,

a murit în condiții suspecte

și e acoperit acum de o cergă verde

cu un verset din Coran,

ceva gen murim cu toții.

Tineri cu geci de piele și părul țepos

se îmbrățișează

în timp ce imamul strigă Allāhu akbar

Allāhu akbar

Allāhu akbar

apoi îl bagă-ntr-o camionetă,

îl leagă cu o centură și pleacă,

aproape călcând o pisică

fără un vârf de ureche.

Ø

Seara se aud focuri de armă.

E sărbătoare. Și protest.

Oamenii aleargă pe străzi și urlă.

Bagabonți de-ai lui Erdogan

și fete islamiste din partidul aliat

șerpuiesc pe șosele.

Ici, colo, o pizdeală.

În cartierul nostru au adus tunuri de apă.

Noapte bună, Turcia.

A friend of his,

an artist,

died in shady circumstances

and is now covered in a green blanket

with a verse from the Holy Quran

something like we’re all gonna die.

Young people with leather jackets

and spikes are hugging each other

while the imam is shouting Allāhu akbar

Allāhu akbar

Allāhu akbar

then they shove him into a van,

fasten him with a belt and leave,

almost running over a cat

missing the tip of its ear.

Ø

In the evening we hear gunshots.

They’re celebrating. Others are protesting.

People are running around chanting.

Young men cheering for Erdogan

and islamist girls from the allied party

are snaking around the streets.

Here and there a brawl.

They brought water cannons in our neighbourhood.

Good night, Turkey.

Dimineața de după.

Mă trezesc pe la prânz,

pe o podea, cu capul umflat -

nici nu mai știu ce m-a pălit.

În jur e scrum peste tot,

deasupra mea un geam spart,

prin care intră miorlăitul unui muezin

și îi trezește pe ceilalți.

Se uită derutați unii la alții,

își amintesc ce s-a întâmplat

și își pun mâinile-n cap.

Se adună în jurul unei mese,

scot un caiet și adună idei:

ce-i de făcut?

Foaia rămâne goală.

The morning after.

I wake up at noon,

on the floor, with a swollen head -

can’t even remember why.

Ashes everywhere,

chants of a muezzin creeping in

through a broken window,

waking up the others.

They look at one another, confused,

remember what happened

and shrug in disbelief.

They gather around a table,

open a notebook and brainstorm:

what now?

The paper stays blank.

Epilog.

Am mers în Turcia anul trecut

la alegerile care au consfințit democratic

regimul dictatorial.

Toți oamenii pe care îi știam acolo

au emigrat când s-au nasolit lucrurile.

Unde să merg?

Cu cine să vorbesc?

I-am zis dilema mea

unui fotograf neamț hardcorist

pe care îl găzduiam în Casa Jurnalistului.

M-a pus în legătură cu un tip pe nume Erman

care mi-a zis că e totul e bine în Istanbul

apoi mi-a trimis revista lui, în care scria

oamenii nu mai protestează

doar se sinucid.

Bucureștiul părea un cartier al Istanbulului

când am pornit într-un autocar plin de hoți și bișnițari

cu gândul că am șanse mai mari decât ei să fiu arestat.

Erman m-a așteptat în portul Kadıköy

și m-a pus în contact cu o mulțime de oameni din scena underground,

apoi a dispărut pur și simplu.

Era pasionat de Cioran și depresiv,

la fel ca mulți dintre cei pe care i-am întâlnit

în acele zile îngrozitoare pentru spiritul liber.

M-am îngrozit și eu

pentru că era o paralelă clară cu ce se întâmpla în România

și în multe alte țări seduse de iliberalism.

Mi-a luat un an să scriu acest poem

ca un tribut pentru revistele lor.

Între timp, România și-a decapitat partidul conducător

Turcia a votat pentru prima oară împotriva lui Erdogan

iar Volkan a publicat un roman SF distopic

foarte apreciat pe insta stories.

Epilogue.

I went to Turkey last year

for the elections that democratically enshrined

the authoritarian regime.

All the people I knew there

left the country when things got nasty.

Where could I go?

Who should I talk to?

I told my dilemma

to a hardcore German photographer

who I was hosting in The House of Journalists.

He put me in touch with a guy named Erman

who told me everything is fine in Istanbul

then sent me his fanzine, which said

people not protest anymore

but commit suicide.

Bucharest looked like a neighbourhood of Istanbul

when I left in a bus full of thieves and smugglers

thinking that I have the best chance of getting arrested.

Erman picked me up in the Kadıköy harbour

and put me in contacts with loads of people from the undeground scene,

then he vanished just like that.

He liked Emil Cioran and was depressed

like many of the people I met

in those horrible days for the free spirit.

I was horrified myself

because there was a similarity to the situation in Romania

and other countries seduced by illiberalism.

I took me a year to write this poem

as a tribute fanzine.

Meanwhile, Romania cut the head of its ruling party

Turkey voted against Erdogan for the first time

and Volkan published a dystopian SF novel

very popular on insta stories.